Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Non classifié(e)

Non classifié(e)

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Project led by

Set up in 2014 the Agency is tasked with formulating and implementing Government’s national policies in the energy and water sectors, aimed at ensuring security, sustainability and affordability of energy and water in Malta.

The Qlejgħa Valley was for a long time abandoned. With the popularity of the valley, known locally as Chadwick Lakes, it has been given a new lease of life, during the latest project that is being carried out. The restoration of the whole area takes into consideration the historical and the environment of the valley. The numerous paths that are used by the local farmers have been upgraded, while a walking trek provides an easy and a pleasant walk along the valley floor. Some of these paths have been upgraded, while others have been re-discovered after the material that had been deposited in recent years, was cleared. These have created a countryside walk, unique for Malta.

The regeneration project aims to rehabilitate the ecological features of the valley. This aims at taking control of the alien species, while increasing the flora and fauna that are characteristic of the area’s environment. Recent ecological studies have confirmed that certain species have increased in quantity, and this helps in the general regeneration of the ecology of the area. One finds several protected trees which are thriving, and with better management, it is believed that their numbers will be increased. Within an olive grove there have been identified a number of wild olive and aged carob trees. These have been scheduled as a Level 1 Area of Ecological Importance.

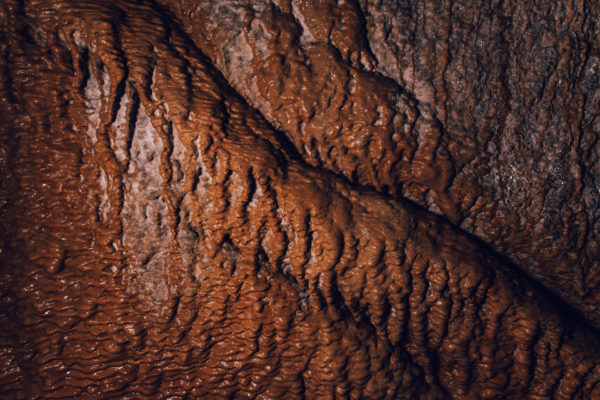

Maltese valleys were carved out by the erosional effect of rainwater runoff and winds through the ages, in particular the pluvial periods associated with the last glacial maxima when Malta was connected to Sicily. During this time, the water passing through the limestone would also carve out these valleys, some deeper than others. The increase in sea level in the Mediterranean, led to Malta being separated from Sicily. This led to a dry period, leading to the drying up of the valleys. Although no large rivers are found in Malta, several streams still continue to provide a spectacle, especially after heavy rain.

Qlejgħa Valley is one of these valleys, rich in vegetation, and forming part of a large valley system, stretching form one part of the island to the shore. It is sometimes referred to as the Għasel system, in which a number of valleys congregate at one end. The stream meanders around the valley floor, forming small pools, or even a small waterfall, wherever there are depressions in the ground. At certain points, streams from different sources join together to provide a larger flow of water. The amount of water present in the valley is very seasonal.

One of the most sought-after areas by Maltese families is the so-called Chadwick Lakes. This area got its name after the intervention of Sir Osbert Chadwick, when during the second half of the 19th century planned several dams, of various sizes and forms, with the intention to retain as much rainwater as possible. Walking along the more than 2 km trail, one would be immersed in rich vegetation, and the sound of water, rushing through the channels, and falling down the dams that were built to retain much of this important source of life. This renders this valley as one of the most interesting and relaxing in Malta.

After heavy rainfall, Maltese families would visit the area, feasting on the natural environment that greets any visitor. The water that would be gathered in the valley floor, would provide a different scenario than any other locations in Malta, making the Qlejgħa Valley, or the Chadwick Lakes, as they are better known, one of the most popular places during the winter months. It is a joy to see children enjoying themselves in this environment.

The trail provides the possibility to walk along the valley floor, surrounded by the natural vegetation, and enjoying a relaxing and quiet moment, making it a pleasure to visit this unique place.

On leaving the premises, turn left and walk up to the crossroad, then take immediately left turn. Keep to the right-hand side of the road, and after a few metres you will notice a large rubble wall, which has been built over the reservoir.

The area around Ta’ Koronja lies above the water table. Thus, the extraction of water from here was important. During the seventeenth century water was used to supplement the Wignacourt aqueduct to take water into Valletta. During the nineteenth century more water had to be extracted and pumped into nearby reservoirs. One of these reservoirs has its walls built to look like field rubble walls, and thus blend in with the rural environment.

On leaving the premises, turn right and take the right-hand road, called Triq Ta’ Bieb ir-Ruwa, and walk along this road for about 2 Km. Take the right-hand road, called Triq Tas-Santi and keep on walking for another 1.6 Km, until you come in front of the gate of the Fort.

This was the first fort to be built along the North-West Front, which was later to be renamed as the Victoria Lines. It started being built in 1875 and was completed three years later. The design of the fort took into consideration the natural escarpment while it was provided with a ditch facing the landward side. Like other British forts of the nineteenth century, within the larger Fort Binġemma there was a smaller, diamond-shaped keep. A drawbridge led into the keep, which was also provided with its separate ditch. The drawbridge would be flanked by musketry loopholes, while caponiers would be built in the ditch.

Leaving the premises, turn left, and walk up the street. Keep to the left and turn sharply left into an unnamed street. This stretch of the road takes one down to the valley floor, and then uphill. Keep on walking along this same stretch of the road, always keeping to the main road. Keep on walking along this stretch of the road, always keeping to the main road. At the start of a downhill stretch, you will soon notice a church on the right-hand side of the road. Next to the church there is a belvedere from where one can see the British 19th century fortifications, forming part of the Victoria Lines. One can take the path located on the right-hand side, to cross over the valley and visit these fortifications. While crossing the valley, one would be walking on the stop-wall of the Victoria Lines.

The Victoria Lines followed the natural escarpment, and this led to the need to the crossing of several valleys. One of these is the Binġemma Valley, and to secure the defensive line a raised passageway was built in the valley. This passageway linked one side of the valley with the other, and soldiers walking on the passageway would be protected by a high parapet facing the valley below. Musketry loopholes were included along this high parapet. Part of the same passageway was hewn in the rock. The passageway built on the valley floor had arches built to allow rainwater to pass through.

Leaving the premises, turn left, and walk up the street. Keep to the left and turn sharply left into an unnamed street. This stretch of the road takes one down to the valley floor, and then uphill. Keep on walking along this same stretch of the road, always keeping to the main road. Keep on walking along this stretch of the road, always keeping to the main road. At the start of a downhill stretch, you will soon notice a church on the right-hand side of the road. Next to the church there is a belvedere from where one can see the British 19th century fortifications, forming part of the Victoria Lines. One can take the path located on the right-hand side, to cross over the valley and visit these fortifications.

In the second half of the nineteenth century, the British military authorities started building and adding fortifications around Malta. Various forts were built and equipped with the latest artillery pieces. A number of forts, an entrenchment and a number of batteries were built in the north-west of Malta, along a natural fault. In 1897 it was then decided to join all these military positions with a continuous entrenchment. These were then called the Victoria Lines, in honour of Queen Victoria’s diamond jubilee. The Victoria Lines are 12 km in length, and they follow the natural high escarpment that divides the north-west of Malta into two. Some of the defence was rock-hewn, while musketry loopholes were added where necessary.

On leaving the premises, turn left and walk up to the crossroad, then take immediately left turn. Keep to the right-hand side of the road, and after a few metres you will notice the ruins of a Maltese farmhouse.

Lying amongst the lush vegetation are the ruins of Ta’ Koronja farmhouse, one of a number of farmhouses in the area. One must imagine the agricultural activity that there would have been in the area, when farming families needed to live near their fields due to the distances with the nearby villages. This farmhouse still has a number of interesting architectural rural features. The arches are an example of the ability of the unknown builders. The outside steps lead to the living area, while the ground floor would be used to store agricultural produce and keep the animals.

The Wignacourt aqueduct can be visited at various localities. The best parts are towards Imrieħel, St Venera and Floriana. Drive towards Valletta on Route 7 and keep to the main road. After about 7 Km, keep to the right onto Triq L-Imdina, and soon after one notices the aqueduct on the left-hand side. The arches continue along the same road, until they reach their end at Sta Venera. The last part of the aqueduct is a tower like structure. There is still another part of the aqueduct at Floriana, just behind the parish church. This is another tower which controlled the water into Valletta.

The building of the new city of Valletta led to the need to provide enough water to its new residents. It was during the time of Grand Master Martino Garzes (1595-1601) that the building of a system to bring water into Valletta was suggested. This did not materialise. Eventually his successor Grand Master Alof de Wignacourt (1601-1622) commissioned Natale Masuccio (c.1561-1619) and the long-awaited project was initiated. The project started by identifying natural springs in the area and had the water channelled towards one large reservoir. Underground tunnels led water towards Attard, but unfortunately Masuccio could not solve the problem of the inclination of the land. A second architect was brought over to Malta, Bontadino dei Bontadini, and this time with the help of Maltese master masons built the aqueduct that finally led water into Valletta in 1615.

In this area known as Għajn Klieb, a cluster of Phoenician-Punic rock-cut tombs were discovered. These overlook the Fiddien Valley. First discovered in 1890, more tombs were subsequently discovered and explored in the following years. One of the most interesting of these tombs was excavated by Sir Themistocles Zammit in 1906, in which he discovered an important Egyptian gold amulet, now exhibited at the National Museum of Archaeology in Valletta. The amulet is made up of two figures showing Horus and Anubis, standing back to back and joined together by a ring. This amulet has been dated to the 7th – 6th century BC. Other tombs in the area provided archaeologists with different types of pottery, helping in the dating of the tombs (Bonanno, 2005).

Malta was the first territory outside Italy that was conquered by the Romans in 218 BC. The main Roman defences were around Melite, the capital city of Malta. Eventually, a number of round towers were built in the countryside. It is difficult to date these structures, as very little material has been discovered within them. Besides the possibility that they were built for defence purposes, it is suggested that could have been built to guard farming estates. Recent studies have suggested that these remains at Għajn Klieb, probably are of a threshing floor.

Leaving the premises, turn left, and walk up the street. Keep to the left and turn sharply left into an unnamed street. This stretch of the road takes one down to the valley floor, and then uphill. Keep on walking along this same stretch of the road, always keeping to the main road. At the start of a downhill stretch, you will soon notice a church on the right-hand side of the road. Next to the church there is a belvedere from where on can see the rock-cut tombs. One must walk down a path, which is located on the right-hand side, to reach these rock-cut tombs.

Carved into the hillside overlooking the valley, are a number of rock-cut chambers which have always been believed to be Jewish tombs. They were first documented by the father of Maltese historiography, Giovanni Francesco Abela (1582-1655) and it was even reported that Hebrew inscriptions were also discovered. Here a number of individual burial hypogea, typical of the rock-cut burial chambers that are found all over the islands, can be found. Sharing the same rock-face, these hypogea have been hewn out of the living rock, and after having been abandoned as burial grounds, some of these would have also been used by local farmers.

On leaving these premises, turn left and start walking uphill. Keep to the left side of the road, cross the road and continue up Triq Għajn Qajjet. Arriving at the main crossroad, keep left, and keep on walking along the same road for another 200 metres. Cross the road and enter Triq G. Galea to the street corner with Triq S Calleja. Turn left and facing you, there is an open unbuilt space where there are these cart-ruts.

Amongst the most mysterious remains from ancient times are the so-called cart-ruts. These are usually ruts carved on the rock surface, and they run in pairs. The grooves are in the form of a V, ending in a slightly rounded bottom. The distance between the two parallel ruts is consistent, although there are slight variations in different localities. These ruts seem to have been some kind of a transport system, although the type of carts or otherwise has been debated. Another difficulty is to which period they belong to. The most favoured periods are either the Bronze Age or the Classical period. There is also the mystery of what these would have been used for, what kind of material needed to be transported over the whole area. As they are found all over the islands, it is difficult to associate them to a particular period. The ones at Mtarfa are clearly cut by a Punic tomb, which might indicate that these date to the prehistoric period.

Leaving the premises, turn left, and walk up the street. Keep to the left, and turn sharply left into an unnamed street, and walk for about 700 metres. This stretch of the road takes one down to the valley floor, and then uphill towards the stone cross, which is on the right-hand side.

There are a number of similar stone-cross at various locations around the Maltese Islands. While they are usually referred to as the Dejma cross, where the local militia would meet in case of an invasion, there are others who maintain that these indicate parish limits. The crosses do not have any features, except that they are usually placed on top of a column, topped with a Doric capital and resting on a circular base. The area is known as Tas-Salib (of the Cross) due to the presence of this stone-cross.

Leaving the premises, turn left, and walk up the street. Keep to the left, and turn sharply left into an unnamed street. This stretch of the road takes one down to the valley floor, and then uphill. Keep on walking along this same stretch of the road, always keeping to the main road. At the start of a downhill stretch, you will soon notice a church on the right-hand side of the road.

The first church was built in 1615 by the nobleman Gio. Maria Xara. Due to the structural instability of the church, a new church was erected in 1685 by a member of the same Xara family. The church was dedicated to Our Lady of Hodigitria, although referred to in Malta as Our Lady of Ittria. The Xara coat-of-arms can be seen above the doorway of the church. This small rural church is well kept, and still in use by the small farming community that live in the area. It commands a wide view of the surrounding valley, fields and coastline. Close by are archaeological and military remains.

Leaving the premises, turn left, and walk up the street. Keep to the left, and turn sharply left into an unnamed street, and walk for about 700 metres. This stretch of the road takes one down to the valley floor, and then uphill towards the church, which is on the right-hand side.

The church was probably built in the 16th century. Its dedication to the Nativity of Our Lady was popular in Malta, especially after the victory of the Great Siege of 1565 as help from Sicily arrived in Malta on 8 September, the feast day of the Nativity of Our Lady. Built in the rural area of Rabat, it would suffer the usual lack of money and furnishings, until it was abandoned sometime in the 18th century. It is a typical countryside rectangular rural church, with a number of waterspouts around it, and a small bell-cot on the façade. Next to the entrance is the usual marble tablet with the words Non Gode l’Immunita Ecclessiastica, thus indicating that ecclesiastical immunity was withdrawn. The church is also referred to as Tas-Salib (of the Cross) due to the presence of the stone cross close by.

Leaving the premises, turn left, and start walking up towards Triq Għajn Qajjet, until you reach the country lane Tal-Markiż. Walk along this path for about 180 metres and turn left and for about 400 metres walk along the same path, amongst fertile fields. The medieval church is on the left side in the middle of the fields.

In the middle of the fields lies the ruins of the medieval church dedicated to St Michael, the Sincere. The Maltese name for this church is of San Mikiel Sinċier, or San Ċir, a corruption of the proper title. A medieval building built in the 15th century, the church was first documented during a visit by Mons. Pietro Dusina in 1575, who reported that the church only had an altar and a pavement. We note that during subsequent visits by the Bishops of Malta, the church was always described as being dedicated to St Michael. Eventually the church was abandoned, and it started to be used by local farmers. The church had a small cemetery on its side.

On leaving these premises, turn left and start walking uphill. Keep to the left side of the road, when you reach the end, cross the road and continue up Triq Għajn Qajjet. Arriving at the main crossroad, keep left, and keep on walking along the same road for another 200 metres. Cross the road and enter Triq G. Galea and continue walking till you reach the playing field. Turn left into Triq Santa Lucija, keep on walking on the left side of the street. The last part of the street looks like a small countryside lane, and soon you will come up on the small church.

The earliest documentary evidence of a church dedicated to St Lucy dates back to the end of the 15th century. It is also known that just before the Great Siege of 1565 it was pulled down, in order to disadvantage the Ottoman army who might use it for their own advantage. Rebuilt afterwards, the present edifice probably belongs to this period. In 1575 it was recorded that the church lacked wooden doors, but it was still functioning. The present building does not seem to have changed much from the 16th century. Its architectural style is medieval, and it has a small apse behind the only altar. The façade has a small window above the only doorway, and a marble tablet with “Non Gode L’Immunita Ecclessiastica” inscribed on it, thus withdrawing ecclesiastical immunity from the church.

On leaving these premises, turn left and start walking uphill. Keep to the left side of the road, when you reach the end, cross the road and continue up Triq Għajn Qajjet. Arriving at the main crossroad, keep left, and keep on walking along the same road for another 200 metres. Cross the road and enter Triq G. Galea and walk for another 1 km. Reaching a pillared entrance, the previous Hospital building is within the school grounds.

After the building of military barracks on Mtarfa hill towards the end of the 19th century, a few years later a military hospital was built close by, instead of a much smaller hospital. This was not the first hospital that the British authorities had built in Malta. A new hospital was commissioned, and construction began in 1915 and completed by 1920. It was named the David Bruce Military Hospital. During the Second World War the hospital was extended to cater for more patients and an underground hospital was also excavated. At its maximum capacity, it had 1200 beds available. The hospital was also used by the Royal Navy and known as the David Bruce Royal Naval Hospital. In 1979 it was handed over to the Maltese Government.

On leaving these premises, turn left and start walking uphill. Keep to the left side of the road, and when you reach the end, cross the road and continue up Triq Għajn Qajjet. Arriving at the main crossroad, keep left, and keep on walking along the same road for another 200 metres. Cross the road and enter Triq G. Galea and walk for about 400 metres, before you turn left into Triq Conti F Teuma Castelletti. Walk along this street for another 1 km, until one comes to the corner with Triq Dar il-Kaptan. Take the right turn, until first turning on the left into Triq Zammit. Second turning on your right, and one comes facing the Isolation Hospital.

Quarantine was a very important health issue in Malta, due to the large number of military personnel stationed here, and the presence of the Mediterranean Fleet. In 1924 an isolation hospital for the British services was inaugurated, close to the main buildings of the Hospital at Mtarfa. The one-storey building follows the typical architectural style of the time, with a number of pilasters and a portico that goes around the façade of the hospital. Large windows provided light to the wards.

On leaving these premises, turn left and start walking uphill. Keep to the left side of the road, and when you reach the end, cross the road and continue up Triq Għajn Qajjet. Arriving at the main crossroad, keep left, and keep on walking along the same road for another 200 metres. Cross the road and enter Triq G. Galea and continue walking into Triq l-Imtarfa till you reach the playing field. Turn right into Sir Leslie Rundle Street and walk along the street, till it joins Triq it-Torri. Turn left, walk for about 120 metres to the Clock Tower.

The Mtarfa Clock tower was built in 1895, forming part of military barracks that were completed a few years earlier. The lower part of the tower is about 22.5 metres high, while the upper part goes for a further 9 metres. Besides some architectural details at the top part of the tower, there are few other such decorations. A spiral staircase leads one up to the top, where the clock mechanism is still located. The clock tower is a dominant feature of the Mtarfa Hill, and it has recently been restored by the Mtarfa Local Council.

On leaving these premises, turn left and start walking uphill. Keep to the left side of the road, and when you reach the end of the road, cross the road and continue up Triq Għajn Qajjet. Arriving at the main crossroad, keep left, and keep on walking along the same road for another 200 metres. Cross the road and enter Triq G. Galea and walk for another 1 km. Reaching a pillared entrance, the previous military barracks are within the present school grounds.

The building of the Victoria Lines and Fort Binġemma required that a large garrison be stationed in the area. This led to the need to build new military barracks to accommodate the garrison. The Mtarfa barracks started being built in 1891 and were completed in 1896. Built on Mtarfa Hill, these barracks offered airy accommodation on spacious grounds. Eventually more buildings were added to the original blocks, and a small hospital with 42 beds was also built. Later the hospital was extended to have 55 beds. The barracks had porticoes providing the necessary shade during the long summer months. Eventually the Barracks Hospital became the Families Hospital, after the larger Mtarfa Military Hospital was completed in 1920.

On leaving these premises, turn left and start walking uphill. Keep to the left side of the road, when you reach the end, cross the road and continue up Triq Għajn Qajjet. Arriving at the main crossroad, keep left, and keep on walking along the same road for another 200 metres. Cross the road and enter Triq G. Galea and walk for another 1 km. Reaching a pillared entrance, St Oswald church is within the present school grounds.

One of the buildings that was erected within the Military Barracks of Mtarfa was a garrison church, built in 1921 and dedicated to St Oswald. The plan of the church is a reduced Latin cross plan, and it has only one altar. It was built to serve the Protestant members of the garrison stationed in Mtarfa. The centrally located bell tower was built at the end of the building, and it is different from what one is accustomed to see in other churches in Malta. The façade and two sides have a veranda going around. After the departure of the British Forces from Malta, the church was converted into a Roman Catholic church, and it is still in use.

All the directions given to the other sites, have the Fiddien Box as the starting point. To reach the Fiddien Box, one needs to reach Rabat, and from the Saqqajja area, follow the signs to The Domus Romana, and keep to the left-hand side. The road follows the valley below, and one is to procced towards a large roundabout, following then the indications to Fiddien. One would soon come up to this Fiddien Box, which was actually a water-pumping station.

Overlooking the Tal-Qlejgħa Valley is a building which was part of the rehabilitation project of the water sources towards Valletta, carried out in the early twentieth century. Making use of the old underground cisterns, built in the seventeenth century and forming part of the Wignacourt aqueduct, the authorities restored channels and made use of metal pipes to supplement enough water to the ever-increasing population in the Harbour area. According to the marble tablet on the façade, the project was carried out during the time of the Governor of Malta, General Sir Leslie Rundle (1909-1915), under the supervision of the Superintendent of Public Works, Lorenzo Gatt (1857-1938), who was responsible for extending and increasing the water supply.

Malta is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, with just about 90 kilometres south of Sicily, and about 350 kilometres north of the Libyan coast. The Maltese Islands have a surface area of 320 square kilometres. The islands are typically Mediterranean, offering little natural resources. Made up of sedimentary rocks which were formed around 30 million years ago, one finds five main geological layers form part of the islands. The clay layer sustains the perched aquifers which contributes to the flow in the valley through springs.

The islands possess natural and deep harbours, which attracted the various traders, mariners and naval powers to the islands. The earliest inhabitants of the islands came from Sicily, and date to about 6000 BC. These first settlers were farmers and introduced agriculture. Two millennia later, other inhabitants of Malta built the magnificent and unique megalithic temples, several of which are still standing.

The various Mediterranean powers eventually ended up colonising and setting up their bases here in Malta. Malta obtained its independence from Britain in 1964. Ten years later the Maltese Parliament declared Malta to be a Republic, and by 1979 all foreign military bases stationed on the island were closed. In 2004 Malta became a full member of European Union.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Phasellus facilisis efficitur magna, vel euismod libero vulputate sollicitudin. Integer sed tincidunt risus. Nam semper ut purus quis blandit. Cras dolor enim, dapibus et faucibus vehicula, volutpat vel eros. Maecenas sit amet dictum risus, vel pulvinar elit. Quisque pretium ligula sed lacus ultricies pretium. Pellentesque aliquam, est eu rhoncus faucibus, ante eros finibus velit, ut pretium massa lacus eu ligula. Aenean tortor elit, tempor id neque vel, volutpat malesuada sem. Ut et libero mauris. Aliquam molestie, urna ut ultrices consectetur, dui nunc tincidunt lacus, quis elementum dui justo vitae neque. Nam erat lectus, volutpat eu mauris pellentesque, fermentum lobortis nunc. Aenean nisi metus, egestas eget massa vel, interdum faucibus justo. Ut molestie, lectus eu sodales mattis, tortor neque volutpat odio, vel maximus risus nulla a lorem.